Just over a year ago, former Nintendo of America President Reggie Fils-Aimé opened up to the public with his autobiography titled "Disrupting the Game: From the Bronx to the Top of Nintendo" (HarperCollins, 2022). In addition to his managerial role, Fils-Aimé has involuntarily remained famous for some memes - "My Body is Ready" is certainly at the top of the chart - as well as for his central presence in the communication of the consoles and video games of the big N : Fils-Aimé's big friendly face lent itself well to presentations and gags in cahoots with the late Nintendo President, Satoru Iwata, and the evergreen Shigeru Miyamoto.

That is why readers were quite surprised to read a triumphalist and very laudatory account of his career, which started from the bottom and reached the top, at the price of certainly inelegant and human considerations (the only thing that stands out is the fact of his divorce, through which hindered his professional career at the time) and an unpleasant background noise: the impression that Fils-Aimé is infallible, within a story whose episodes are carefully selected to capture the undoubted abilities of a man who never has to ask.

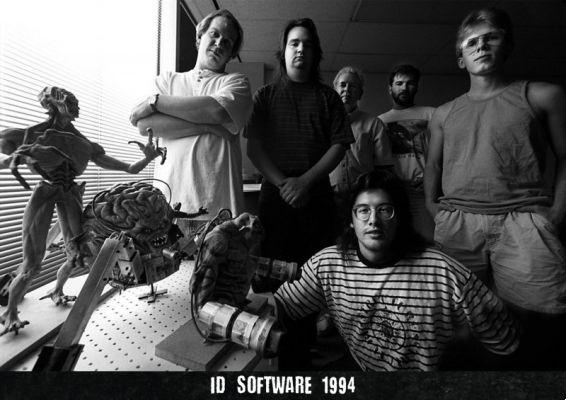

Here, in this sense "DOOM Guy. Life in first person" (Abrams Press, 2023), recently published, is a breath of good, effervescent air from a long-time developer, John romero, which at the dawn of its fifth decade in the gaming industry is not afraid to look back. And he does so by acknowledging mistakes, faults and glaring omissions, as well as celebrating the talent of him and his collaborators, recalling some of the most important and memorable moments in the history of the medium. If the crunch of the "death schedule" in id Software is sometimes sweetened thanks to the point of view of the then young Romero - a person undoubtedly eager to learn and succeed, co-founder of the studio and therefore directly interested in the outcome of his projects - the book clearly surpasses other stories of lives in the sector, and above all the volume by Fils-Aimé, thanks to a flowing and no-frills style, in addition to the aforementioned honesty of the author in recognizing responsibilities which, in the case of Ion Storm, led to the closing of the studio.

There is still some regret for the brief account of the last fifteen years of Romero's activity, but it is clear from the title that the autobiography wants to first explore the years that interest fans the most: those of the emergence of id Software. , his professional divorce from the exceptional team he helped create, and the disastrous fall of Ion Storm. But let's delve deeper and explore the meteoric career of the man who calls himself "DOOM Guy," because Romero may be best known for the deadly shooter developed with John Carmack and associates, but his path is much more layered and plural than you can imagine. seem. at first sight.

Know how to forgive, know how to forgive yourself

The first part of the book, dedicated tochildhood of little Romero and the description of his relatives. Not everyone knows that his baptismal name is Alfonso Juan Romero: Alfonso was also the name of his father, a central figure in the life of his son and evoked repeatedly during the autobiography. The behavior of Alfonso, a first-generation Mexican-American, is responsible for the only very harsh moment in the volume: his Domestic violence, of which alcoholism is a sad accomplice, are described by Romero in a moving way, full of regret for a man who died prematurely due to a life of addiction to alcohol and drugs.

Despite everything, the father figure is remembered with great affection: "Everyone loved him. I loved him. Alcoholism and addiction defined his death, but they did not define his life. My father was so many things to so many people" (p. 435 ) [Editor's note: for ease of reading, the excerpts from the book proposed in this article are my own translation. At the time of writing this article, "DOOM Guy. Life in the First Person" is available exclusively in English, and therefore there is no official Spanish version.] Among the few objects his father owned at the time of his disappearance, John Romero found a small folder with a article about your son's successes, already famous and acclaimed around the world at the time.

Perhaps the main message of "DOOM Guy" and Romero's story as a whole is this: If even one parent responsible for domestic abuse can be saved from summary conviction and fondly remembered, then we can all benefit from anon-judgmental analysis of own and others' behaviors. Even when recalling the cold "report card" sent by John Carmack to his colleagues to complain about the team's (in his opinion) poor performance during the development of Quake (id Software, 1996), Romero shows understanding for Carmack's discomfort and his regret for not being able to respond adequately: on that occasion, the other team members decided not to act on the programmer's complaints and go their own way. “It saddens me to think how [John Carmack] must have felt when he sent the report and received no response” (p. 316), he writes.

There is certainly bitterness in telling the sad descending parable of Ion storm, which he founded in 1995 with his former partner (and great friend) Tom Hall. Given the "disaster" (as he defines it on p. 365) that was Ion Storm, Romero opens the portion of the volume dedicated to his company by acknowledging that he has learned a lot from his journey, and stating that he hopes that the lessons he learned the hard way They may be useful to readers. Romero fully recognizes his responsibility in approving the controversial Daikatana advertisement (Ion Storm, 2000), based on the writing "John Romero is about to make you his bitch. Suck it", full of deathmatch language that is completely inappropriate for marketing.

"When I was a kid, when things went bad, out of necessity, I was good and waited for that moment to pass. When Carmack sent in his report, I was good and waited for that moment to pass. When several people told me they were unhappy I was good and I waited for that moment to pass. Everything that happened to Ion Storm is a direct consequence of this character flaw of mine. If I had acted, if I had talked to these people, if I had prevented the growth of the problems that were emerging, so many "Things in my career and in my life would have been different and so many people could have avoided the difficulties generated by this defect of mine" (p. 424), writes Romero. As for the author of that terrible advertisement, he was a man destined for greater undertakings. : Mike Wilson, CEO of the company at the time, would co-found, in 2009, none other than Devolver Digital. But, as they say, that's another story.

Regarding the sensational disruption of id Software's balance and his ouster from the studio he helped found, John Romero firmly disputes many of the accounts that have emerged about the episode over the years. Excerpts from "Masters of Doom: How Two Guys Create an Empire and Transformed Pop Culture" by David Kushner (Piatkus, 2003) are cited on several occasions, although the book, perhaps the best known in the reporting scene, is often cited. about video game development. , is taken as an implicit reference point to correct - always with grace - stories judged incorrect, exaggerated or out of focus by those who experienced them firsthand. Romero recalls that the id Software divorce did not lead to long-term feuds and was much less dramatic than it was often portrayed, as he also confirms. John Carmack in the memorable August 4, 2022 episode of Lex Fridman's podcast. Carmack, along with the entire original id Software team, is remembered in the affectionate acknowledgments at the end of the book.

Not just the DOOM type

It is a shame that John Romero's autobiography focuses almost exclusively on the years of his career for which the greatest amount of documentation already exists. Books, interviews and documentaries have been dedicated to the events of id Software and Ion Storm: the perspective of one of the protagonists has a unique value, but Romero is much more than the "DOOM boy" to which the title of the volume also refers. And to think that the famous developer is perfectly aware of having an attentive, passionate and enthusiastic community... In the literal sense: in every public appearance, Romero is surrounded by ecstatic fans who bow before him, repeating "We" over and over again. "You are not worthy."

Romero Games would have deserved more attention. The recent Empire of Sin (Romero Games, 2020) is completely overlooked, while co-founder Brenda RomeroTo , John's wife and, in turn, a very important figure in the world panorama of video game development, few thoughts are dedicated to her, except for the dedication of the book. She mentions the project currently underway at the studio, a first-person shooter that will represent "a new dawn for Romero Games," as we read on the company's recently revamped website. There would be a lot to say: as an example, corporate policy leads all full-time employees of the company to own a part of the company, creating an identification (although partial and still rare) between corporate ownership and "worker." grassroots", a model encouraged by all the most recent trade legislation in the Western world.

There is no doubt that John Romero's autobiography could have been enriched with some more reflections on the mechanisms - not always virtuous as in the case cited above - of the world of video game development. The parts dedicated to "death schedule" of work in id Software, from 10 in the morning to 2 in the morning, are sometimes sweetened by the description of the burning passion of Romero, Carmack and associates; ultimately, the crunch policies of development studies do not receive an adequate and firm condemnation for what they are, i.e. practices contrary to the labor law disciplines of any civilized country. Romero seems to regret these policies only when the work environment at id Software becomes unsustainable, when he is close to the release of Quake and Carmack decides to move the work to "War Room" (a name, a program), with the imposition of a tough crisis of at least twelve hours of work to conclude Quake. On the contrary, the first period of overwork in the studio is remembered as a period of rapid learning and camaraderie between those who, without a doubt, were true development geniuses, destined to change the history of the medium; The risk, however, is that of inducing phenomena of imitation - which will almost never lead to remotely similar results - and of veneration of practices capable of destroying the personal lives of many individuals.

This is, in all respects, a wasted opportunity to take a clear position on the practices described, in all their cruelty, from the book as "The Rise of Video Game Fandom: How Fans, Normals, Hobbyists, Artists, Dreamers, Dropouts, Queers, Housewives, and People Like You Are Taking Back an Art Form" by Anna Anthropy (Seven Stories Press, 2012), "Blood, sweat and pixels: the triumphant and turbulent stories behind how video games are created" (HarperCollins, 2017) and "Press Reset: Ruin and recovery in the video game industry", between Jason Schreier (Grand Central Publishing, 2021), from which I warmly advised the literature.

Without these criticisms, "DOOM Guy. Life in the first person" is a book that any fan of the videogame medium should read. Extremely editorially accurate (typos can be counted on one hand), easy to read, and heartfelt (almost always) when necessary, John Romero's autobiography charts the growth path of a boy who gradually became a superstar. Twenty years old, winner of a surreal Monopoly video game without even passing the exit, he becomes an adult looking back with serenity and recognizing his mistakes. Romero describes the writing of this book as a "transformative process" (p. 424): The same can also apply to readers capable of grasping the underlying message. And loving yourself also means forgiving other people's defects, and especially your own, looking inside yourself with honesty and indulgence at the same time.