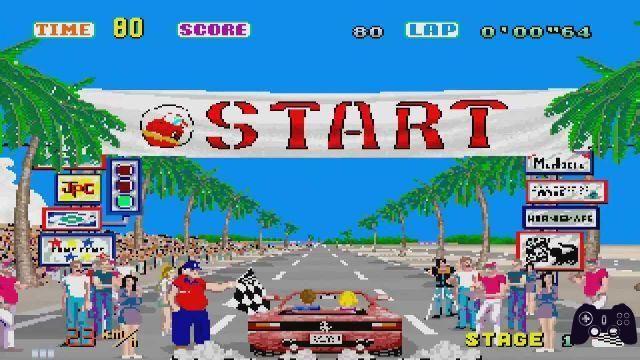

An endless road, a Ferrari and the pure pleasure of driving. A timeless and timeless journey, today as then.

The second of the two examples of Ferrari Testarossa Spider, after the one built specifically for the lawyer Gianni Agnelli, it was the one donated by the Maranello house to Yu Suzuki, virtualized and then shared to become a cultural icon of the video game, of an opulent and thoughtless historical period, hidden under a carpet of 16-bit colors, chiptune and traffic violations, for the greater glory of freedom. 1986, OutRun, Magical Sound Shower, a love story at 290km / h enclosed in an infinite loop, as eternal as the road that unrolled under the steaming tires of the red 12-cylinder goddess, while the sky was painted in every shade of color imaginable and the seasons changed from junction to junction. The work SEGA it is wealth and well-being, the illusion of the 80s arcade racing format, immortal like a historical event, current like a work of art. The manual gearbox, the overtaking to the limit, the anxious hourglass overhead in continuous conflict with the need to properly set the curves, are all elements that make OutRun a classic capable of teaching and giving life to an entire trend that this month reached its techno-playful peak with the fourth iteration of the Forza Horizon series, a signed summa Playground of all the best the genre has offered in the past 30 years. We turn on the engines, turn the saturation to 100 and turn up the volume to honor arcade racing.

Motoring becomes synaesthesia

If the simulation succeeds in entrancing and enhancing what we feel in the reality of everyday driving, synthesizing it and enhancing it in terms of speed and means, the arcade suspends disbelief and mixes perceptions, playing with the sounds, with the colors of locations between real and surreal and with driving styles deliberately brought to the excess of dynamics to allow the player to experience a spectacularity that is as impossible as it is extremely satisfying and seductive. It is no coincidence that the first high profile work of Tetsuya Mizuguchi, philosopher of synaesthesia applied to video games (let's talk about stuff like Rez, Lumines, Child of Eden) was the cabinet of SEGA Rally, arcade racing on dirt par excellence, equipped with air suspension and speakers directly installed in the headrest to enjoy the phenomenal fusion rock of the title, often embellished with bass lines that would have made Flea pale (or maybe not, but the style is that). It is precisely the Tokyo house that was the protagonist of the genre in those years, thanks to designers and musicians who beatified hardware and cabinets to give life to excellences such as Daytona USA and Virtua Racing, still current for mechanics and polygonal motors still beautiful and out of the conception of time as if they were in 2D.

Softness on canvas, aesthetics and counter-steering.

But above all it is the all-Japanese taste for drifting and for the mistreatment of the rear tires for the greater glory of oversteer to act as a common denominator to this videogame trend that will involve other developers like wildfire (of the engine), above all Namco and a series that openly challenges physics and its most basic logic, pushing the player to always drive to the limit: Ridge racer, in the same year as Daytona, 1993. Here the car totally loses friction with the ground and the driving becomes figure skating, leaving on the asphalt a bit of the elegance of the classic SEGA, like a black strip of burnt rubber, differentiating itself for a particular mood that began to detach itself from the 80's taste (even in the sounds, here decidedly more electronic, techno) to finally embrace the new decade, but above all for an engine always at maximum revs, planted on 60 frames per second of the his cabinet. The third installment, Rage Racer, 1996, will also mark the first appearance of Reiko Nagase, mascot / pin-up of the Pac-Man house that will immediately become an icon of the racing video game. Women and engines, it is proverbial.

The progressive abandonment of the arcades by the players and the arrival of a new generation, performing as never before, is, however, about to mark a decided change of course, a J inversion with burnout - and Burnout - that projects the genre into the new millennium.

Simulative contamination and criminal drifts

The sixth generation is reality, the racing world begins to tend towards aesthetic realism, abandoning its synesthetic amalgam. Even SEGA on Dreamcast launches the good SEGA GT, Yamauchi's personal response to the success of Polyphony on the Sony flagship, and the genre changes shape by marrying realistic elements, now more within reach of technology. This is how new hybrids are born that look above all to the underground scene of clandestine racing in the midst of civilian traffic (driven by the first Fast & Furious of course), in a videogame industry upset by that Grand Theft Auto 3 that changed it forever. Burnout, Need For Speed Hot Pursuit 2 and later Underground, in which the criminal heart of the Chase hq. of Taito than the carefree one of OutRun. A sign of the times, like a virtual thermometer of society. There is the challenge with the police or the identification with them, a "guard and thieves" that is repeated and alternated in the various episodes of these brands. You drive with less bite, you pay less attention to trajectories, caught in the rush to eliminate opponents or caught in the vicious circle of aesthetic changes to your Toyota Supra, forced into mainly city, squared and syncopated circuits in which, however, the old school arcade element survives in some design choices, such as scoring and time limits. But it is Burnout 3: Takedown that really changes the cards and innovates, becoming a perverse demolition derby at 200km / h. The road accident becomes art, the cars are glued to the ground as if they were Formula 1 and become real weapons of mass collision.

This derivation of the Criterion series becomes a real cult, a new way of interpreting the stylish gameplay applied to arcade racing, in the wake of titles inspired by extreme sports, from Tony Hawk to SSX but declining it to action, here as important as talent behind the wheel. A Daytona from the penal code that gives a shoulder to the genre and to the opponents, along a parallel road, strictly in the opposite direction, to those who on the first Xbox, since 2002, are managing to maintain a certain purity of meaning that does not ignore the passage of years . Bizzarre Creations launches Gotham Racing exclusively for the Redmond Project house (PGR), who with his Kudos it will influence the other software houses, Criterion pre-Takedown in the first place, creating a memorable simcade that will become the basis for those who want to develop an arcade-style course in the years to come. Still immature in its first iteration and constantly growing, PGR forces the player to run with style and cleanly, overtaking in braking rather than engaging in a duel of doors, under penalty of deduction of the Kudos accumulated with the previous circus number not yet " revenue". Everything that can be done behind the wheel thus becomes a reward, drawing from classic coin-op mechanics such as checkpoints to extend the time available, right in the year of the downsizing of the post-Dreamcast SEGA. Simulation physics blends with typically enjoyable driving ease, licensed luxury cars shine thanks to wax-polished polygons and city tracks remain a fixed point, even if strictly closed to traffic. Fast forward until 2006, the year of the third chapter of the series, the first on Xbox 360, of course, but above all of a past that perhaps ends definitively and of a futuristic experiment that will lead us to an extraordinary present.

Death and rebirth of arcade racing

OutRun 2006: Coast to Coast. These characters are enough and advance to enthrall the enthusiast and induce him into addiction with a constant release of endorphins from travel to travel, videogame and mental. Best outrunner ever, unsurpassed and unsurpassed, a masterpiece that SEGA has entrusted to one Sumo Digital in a state of grace that takes and integrates into the OutRun 2 project in the cab version and fills it with extra content. It is one of those titles to bring to the phantom desert island, a videogame sugar dispenser with which to fall into an insulin crisis. A collection of stratospheric Ferraris, original tracks remastered as they deserve (without detracting from the wonderful original chiptune, but here we are at an exceptional level of composition) as well as specially engraved new entries (Life Was a Bore is a piece of rare beauty), two separate campaigns branching off at crossroads as tradition dictates and a warm, vibrant, timeless aesthetic.

The pinnacle of a genre, of a series, of a splendidly and excessively erotic vision of drifting, reached exactly 20 years after Suzuki's cultural must, the apotheosis of glory before the abyss. Too anachronistic and out of the market OutRun, the masses want more, they want freedom of movement and photorealism. Come back Test Drive, after an identity crisis that lasted several years, and the episode Unlimited it is pioneering. 1600km of viable roads on the spectacular island of Oahu, Hawaii, a detailed open world full of content, cars, challenges, which sinned for a fairly bland driving model compared to all the competitors, which made it gray enough to roam freely for a map almost empty of content other than the points of interest corresponding to the races, focusing almost everything on an online structure shared with other users. It is the sin of many titles that they are too far ahead of their time, then unknowingly becoming the basis for something much more glorious, refined. In fact, another 6 years will pass, and then another 6, to see not only the ideas of Test Drive resurrect, but those of the entire arcade racing scene of the past 30 years. Playground and Forza Horizon, born as a spin-off of the highly simulated Turn 10 Motorsport, one of the spearheads of the Microsoft exclusive park. Forza Horizon is the arcade bible applied to modern technologies supported by a “triple A” budget. Motor magic that encompasses, with class and delicacy (the mini story of streamer @LaRacer in Forza Horizon 4 is a tearful one), everything that has been this niche over the years and everything that has been written here.

Cars and nature, sensual models.

6 years and 4 chapters in which you pass seamlessly from the romantic pleasure of the aimless journey, while stars and seasons alternate outside the window, sea and mountain views, countryside and city, to the tightest and most hardcore competition embellished by Drivatar technology that steals the driving style of users to fill the polygonal shells of the opponents in single player; from the scoring hunt, reverent towards Project Gotham (a bit like all its basic structure) and refined on the combo system of the action made in PlatinumGames, to the online multiplayer, competitive, cooperative, shared, taking the best of modern open world content and sterilizing downtime with a driving model that's pure fingertip balm, transforming everything into fun and giving life to an almost Nintendian world design. A continuous crescendo in which Playground has filed, corrected and added, from time to time, passing from Colorado to the Cote d'Azur divided between Italy and France, from the thousand Australian colors to the British seasons. Horizon is the resurrection of a genre that outside the indie scene (the excellent Horizon Chase Turbo is an effective palliative, 90s Super GP await) will no longer be that of 1986, capable of leaving aside nostalgia to make us accept with its beauty the new course of this discipline, finally returning a synaesthetic experience where touch, hearing and sight whirl in a centrifuge of emotions with a high octane rate.